We are/I am neither solely circles nor points, but lines that curve, loop and knot into each other—scaled variably. Passing the pattern from one to another, a finger catching a skein before another takes it on. We’ve misplaced our rulers, pointing machines, leaving straight flight-paths for collective deformations/distortion: to learn to do the time warp again, to feel the lag, the delay, the drag, the swerve, the rush, the eddies. Lingering in the warmth of friction that comes with motion, we give attention to these moments as a way of developing protections and permeabilities, amplifying affinities and noticing differences, kinds of care and sharing. Orientated by waste, meshes, scores, and broken windows, possible gatherings and i/solations. Being beside ourselves and one another.

![]()

![]()

Conceived through interweaving lines of research, and the interest of amplifying research through collaboration and collective gathering, we present work and ways of working across disciplines, through openings into new signifying worlds stranded in this gulf of time, an interregnum examining how we are entangled together and with others. Becoming a space with .space without space.

As part of soft/WALL/studs’ month-long research period with Cemeti - Institute for Art and Society, the project 'In a Hard Place Apply Soft Pressure/s' forms positions and superpositions, adaptations and maladjustments, with individuals and objects both close and distant, through re-appropriation of materials, collaborations, contaminations, boundary crossings, pulling and relaying an archive of forms and gestures among themselves as a way to revisit and reroute strategies and formats among themselves.

surfacing and resurfacing > double-agency and mimicry ~continuity, bleeds, and breaks *

Conceived through interweaving lines of research, and the interest of amplifying research through collaboration and collective gathering, we present work and ways of working across disciplines, through openings into new signifying worlds stranded in this gulf of time, an interregnum examining how we are entangled together and with others. Becoming a space with .space without space.

As part of soft/WALL/studs’ month-long research period with Cemeti - Institute for Art and Society, the project 'In a Hard Place Apply Soft Pressure/s' forms positions and superpositions, adaptations and maladjustments, with individuals and objects both close and distant, through re-appropriation of materials, collaborations, contaminations, boundary crossings, pulling and relaying an archive of forms and gestures among themselves as a way to revisit and reroute strategies and formats among themselves.

surfacing and resurfacing > double-agency and mimicry ~continuity, bleeds, and breaks *

off-worlds and outposts #

subterraneans + under-ings } affinities and intimacies collectivities beyond the collective ^

disorientations and off-temporalities `

intersections and entanglements % extreme corners, soft corners

Bluelight Transition Management

These are the blues, the double ticks and double binds that simultaneously index attachment, concern, intimacy, expectation, care, neglect, inaction, self-protection, individuals entangled by their related projects and lives. This is specific to me/us, and also shared as generic conditions.

There are several hues and kinds of blues:

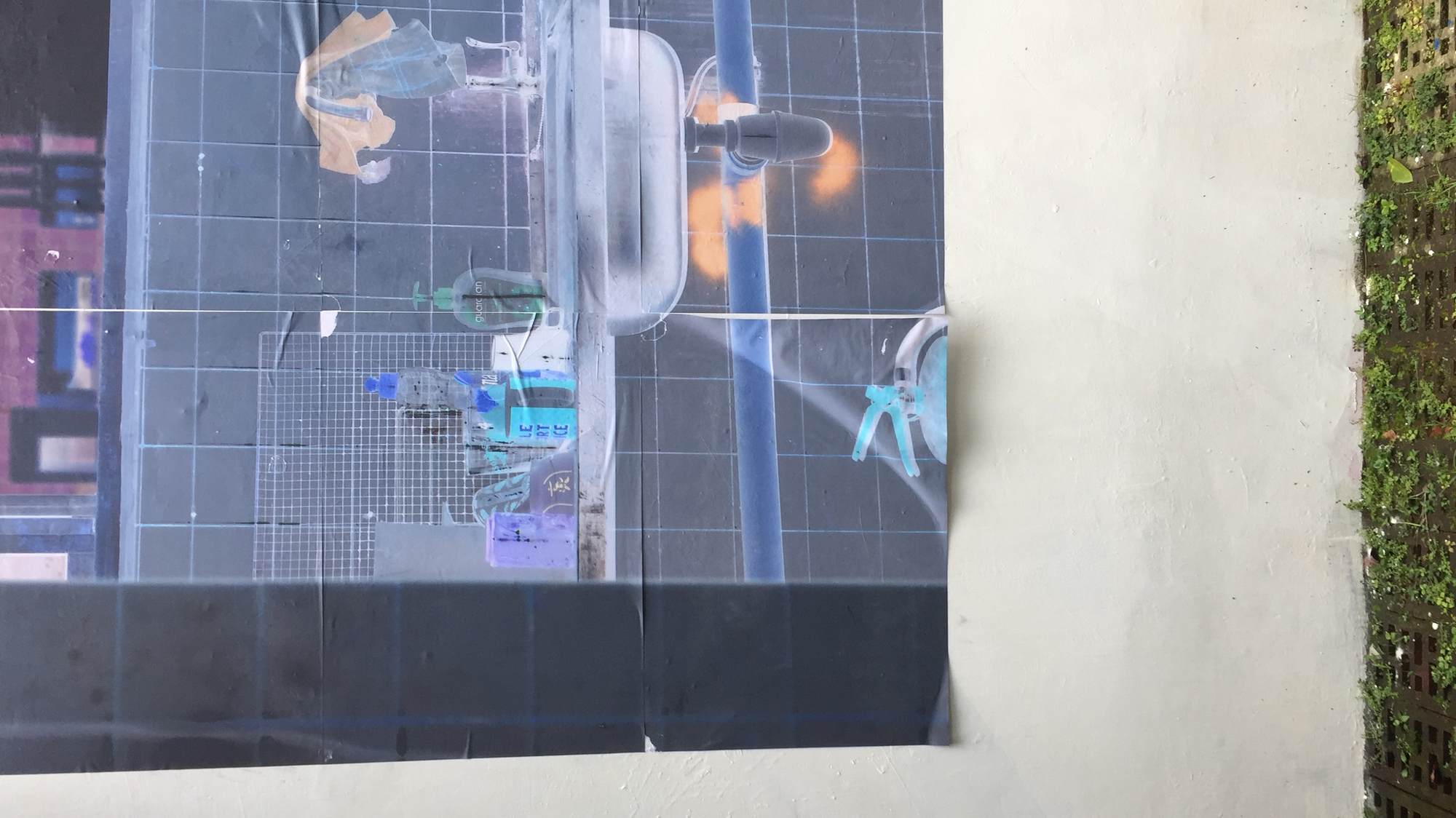

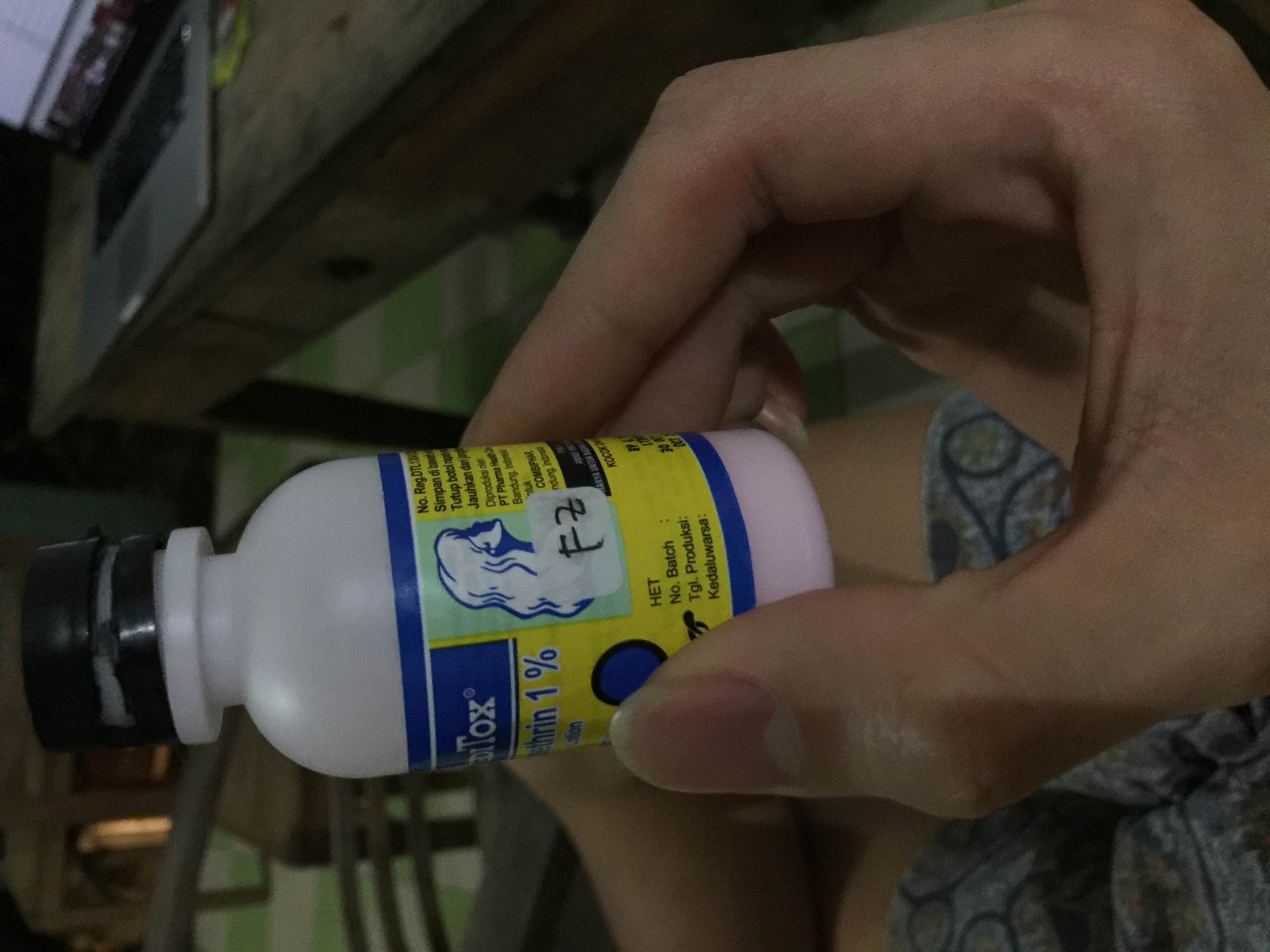

Blue spray for cockroach management (inverted via negative to orange)

![]() a photograph of the kitchen area wheatpasted on the external walls of the Cemeti Institute for Art and Society

a photograph of the kitchen area wheatpasted on the external walls of the Cemeti Institute for Art and Society

An ectoplasmic viscera, orange hued, strikes out from the print outs of the kitchen sink like a trick of light.

During one of those lonesome nights at s/W/s (circa 2016, no-one for miles, for days), I saw a cockroach scuttle across the tiles beneath the sink. I jumped up and tried to find something to kill it. At home, my parents had developed a soap spray they spritzed at cockroaches. Cockroaches don’t have lungs, but instead possess breathing mechanisms called spiracles. Clogging those spiracles with soapy water is a way to drown them. I found the next closest spray -- a pressurised, Nippon Sky Blue. I barely hit the cockroach; slightly weakened it dropped off into a corner and was squashed a couple days later by a friend.

The lurid squiggle the spray makes is a very specific kind of blue. It is also, in its inverted, printed form, a hieroglyph to most but a punctum to me. It is an afterimage of effort. This blue is neither morose nor hopeful -- not the blue of melancholy or the romance of distance. No, it is the clinical, sharp blue of authentication, security, and maintenance. The drawing of a border. An assassinating mark. It says, I have felt this place as mine, not all the earth is your deathpit, roach, to crawl about and eat in. To spray is to show I have developed some feeling for property over this space; the cockroach may be crawling on white tiles but it might as well be crawling on my very skin. Here marks the human stain, the human strain.

Bluetick management:

Blue ticks cross and subdivide, skate infinity-eights around yourself. Herein lies the doublebind of double-agency: you do the work of both yourself and what is shared.

![]()

I am in nearly every single group chat from every project we have done for/with/around s/W/s. Two days after our opening, during brunch, I disrupt my meal and conversation with Ken (we were the last two left in Yogja) by replying to at least two of these groups. As you must: you have been marked by blue, the blue of the beginning and the blue of the present. This does not mean everyone else feels as bound by the blue markings; in fact others set boundaries, and make sure the blue ticks never register.

A mildly acquainted person texts your private facebook account about the space, asking if they can register for an event via your person, even though the event page clearly asks everyone to email. Make no mistake, while the entity exists, human bodies are the hard targets which others can register as openings. And your discernibility, your person as passageway, is what registers the labour. You have liked this intimacy before, this funny thing created between you and others. Each visitor seemed less anonymous. You could make this encounter special. But now this intimacy irrirates you and you wonder if it is intimacy at all. Because the space is read as immensely private, and perhaps it seems the only way to enter as an outsider is to pretend some kind of intimacy. You catch requests making associations to knowing some of your friends. You know it is untrue. You decide you would answer robotically, clinically, the default phrase: “Please send all requests to our shared email”.

The question: how are you made present? How are you bound to others within the space and outside of it? How have the structures of the space enabled a kind of closeness without closeness, a closeness which also means splintering, and a closeness that could wear you down and affect the sustainability of labour?

Well, you could say, these are things you could recalibrate. You can choose your labours, choose your implications. You can correct course and correct expectations. But what how can we know anything beyond the blue horizons of our binds?

These are the blues, the double ticks and double binds that simultaneously index attachment, concern, intimacy, expectation, care, neglect, inaction, self-protection, individuals entangled by their related projects and lives. This is specific to me/us, and also shared as generic conditions.

There are several hues and kinds of blues:

Blue spray for cockroach management (inverted via negative to orange)

a photograph of the kitchen area wheatpasted on the external walls of the Cemeti Institute for Art and Society

a photograph of the kitchen area wheatpasted on the external walls of the Cemeti Institute for Art and SocietyAn ectoplasmic viscera, orange hued, strikes out from the print outs of the kitchen sink like a trick of light.

During one of those lonesome nights at s/W/s (circa 2016, no-one for miles, for days), I saw a cockroach scuttle across the tiles beneath the sink. I jumped up and tried to find something to kill it. At home, my parents had developed a soap spray they spritzed at cockroaches. Cockroaches don’t have lungs, but instead possess breathing mechanisms called spiracles. Clogging those spiracles with soapy water is a way to drown them. I found the next closest spray -- a pressurised, Nippon Sky Blue. I barely hit the cockroach; slightly weakened it dropped off into a corner and was squashed a couple days later by a friend.

The lurid squiggle the spray makes is a very specific kind of blue. It is also, in its inverted, printed form, a hieroglyph to most but a punctum to me. It is an afterimage of effort. This blue is neither morose nor hopeful -- not the blue of melancholy or the romance of distance. No, it is the clinical, sharp blue of authentication, security, and maintenance. The drawing of a border. An assassinating mark. It says, I have felt this place as mine, not all the earth is your deathpit, roach, to crawl about and eat in. To spray is to show I have developed some feeling for property over this space; the cockroach may be crawling on white tiles but it might as well be crawling on my very skin. Here marks the human stain, the human strain.

Bluetick management:

Blue ticks cross and subdivide, skate infinity-eights around yourself. Herein lies the doublebind of double-agency: you do the work of both yourself and what is shared.

I am in nearly every single group chat from every project we have done for/with/around s/W/s. Two days after our opening, during brunch, I disrupt my meal and conversation with Ken (we were the last two left in Yogja) by replying to at least two of these groups. As you must: you have been marked by blue, the blue of the beginning and the blue of the present. This does not mean everyone else feels as bound by the blue markings; in fact others set boundaries, and make sure the blue ticks never register.

A mildly acquainted person texts your private facebook account about the space, asking if they can register for an event via your person, even though the event page clearly asks everyone to email. Make no mistake, while the entity exists, human bodies are the hard targets which others can register as openings. And your discernibility, your person as passageway, is what registers the labour. You have liked this intimacy before, this funny thing created between you and others. Each visitor seemed less anonymous. You could make this encounter special. But now this intimacy irrirates you and you wonder if it is intimacy at all. Because the space is read as immensely private, and perhaps it seems the only way to enter as an outsider is to pretend some kind of intimacy. You catch requests making associations to knowing some of your friends. You know it is untrue. You decide you would answer robotically, clinically, the default phrase: “Please send all requests to our shared email”.

The question: how are you made present? How are you bound to others within the space and outside of it? How have the structures of the space enabled a kind of closeness without closeness, a closeness which also means splintering, and a closeness that could wear you down and affect the sustainability of labour?

Well, you could say, these are things you could recalibrate. You can choose your labours, choose your implications. You can correct course and correct expectations. But what how can we know anything beyond the blue horizons of our binds?

It is raining here. It should be raining over there too. I look at the clock, and then at the calendar. Fuck. There’s not much time for anyone. Not in this context, and definitely not in this climate. This climate -- all of it.

Cain sent us a photo of Marcus rummaging around in the green. His back is turned in the picture, and he is hip-high in grasses and stone ruins. I don’t know nearly enough about Yogjakarta to place him. Up it goes on the instagram page. It is an image of release from the images before, of the dark haunted interior of s/W/s cluttered with his globes.

I did this to myself. This lack of time. I convinced myself of my goodness. By going for only twenty two days I will assuage a father already ill with cancer that I have less time to contract malaria or fall into a crevice during an earthquake (there was an earthquake on Java last month ...) Between cancer and the assails of natural disaster there is only so much contingency a body, linked or a lone, can stand. It’s not bourne alone, energy, disease, anxiety spills over, is shared by supports. It winds itself into you too; something sacrifices, you bend, you absorb. But perhaps there is another way -- to refract?

Old wounds, old contentions. Blindsided by them. I’m also blindsided by the blink of time coming my way. How does a body withstand all of this and allow itself transport into another context, to absorb its feeling, its histories, allow it to work yourself into you? Perhaps the question is not about withstanding but about absorption. About expanding. About allowing.

And erecting checkpoints. You are coming with a history ...

(Luca)

HOME

Cain sent us a photo of Marcus rummaging around in the green. His back is turned in the picture, and he is hip-high in grasses and stone ruins. I don’t know nearly enough about Yogjakarta to place him. Up it goes on the instagram page. It is an image of release from the images before, of the dark haunted interior of s/W/s cluttered with his globes.

I did this to myself. This lack of time. I convinced myself of my goodness. By going for only twenty two days I will assuage a father already ill with cancer that I have less time to contract malaria or fall into a crevice during an earthquake (there was an earthquake on Java last month ...) Between cancer and the assails of natural disaster there is only so much contingency a body, linked or a lone, can stand. It’s not bourne alone, energy, disease, anxiety spills over, is shared by supports. It winds itself into you too; something sacrifices, you bend, you absorb. But perhaps there is another way -- to refract?

Old wounds, old contentions. Blindsided by them. I’m also blindsided by the blink of time coming my way. How does a body withstand all of this and allow itself transport into another context, to absorb its feeling, its histories, allow it to work yourself into you? Perhaps the question is not about withstanding but about absorption. About expanding. About allowing.

And erecting checkpoints. You are coming with a history ...

(Luca)

HOME

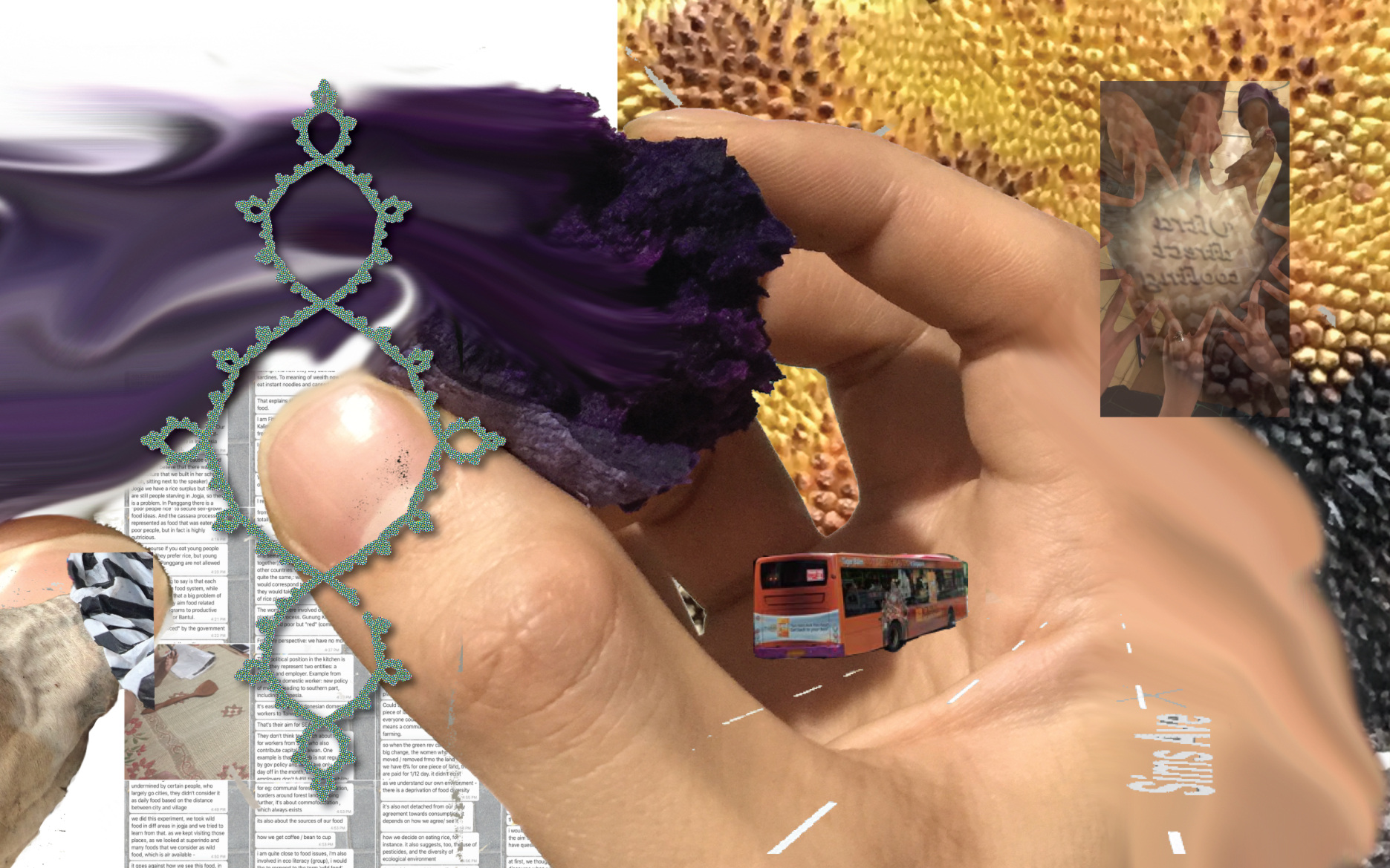

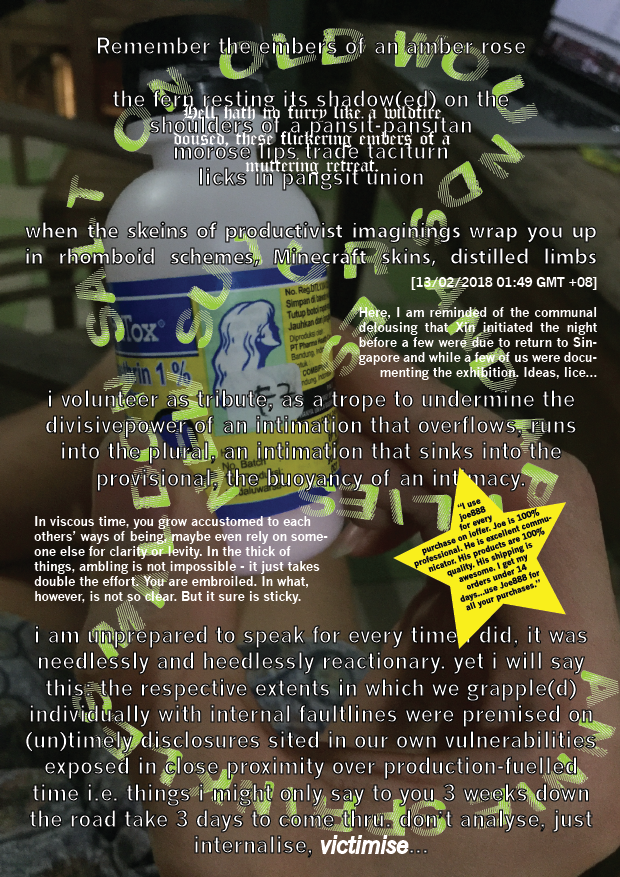

Remember the embers of an amber rose

the fern resting its shadow(ed) on the shoulders of a pansit-pansitan

morose lips trade taciturn licks in pangsit union

when the skeins of productivist imaginings wrap you up

in rhomboid schemes, Minecraft skins, distilled limbs

i volunteer as tribute, as a trope to undermine the divisive

power of an intimation that overflows, runs into the plural, an intimation that sinks into the provisional, the buoyancy of an intimacy.

i am unprepared to speak for every time i did, it was needlessly and heedlessly reactionary. yet i will say this: the respective extents in which we grapple(d) individually with internal faultlines were premised on (un)timely disclosures sited in our own vulnerabilities exposed in close proximity over production-fuelled time i.e. things i might only say to you 3 weeks down the road take 3 days to come thru. don’t analyse, just internalise, victimise...

*annie sprinkles maldon salt on old wounds and applies new sutures

“ I use joe888 for every purchase on ioffer. Joe is 100% professional. He is excellent communicator. His products are 100% quality. His shipping is awesome. I get my orders under 14 days...use Joe888 for all your purchases.”

there is no joe888 or youtiao666 in the embers of a dying rose. no points to be scored, no games to be won, only magical thoughts you can slip under your paws. there is no fade into the bg or wallflower selfies (t)rolling up in the throes of “partition, please”, no marketing of second-guesses, no unpacking of serfdoms, only hawking secondhand anxieties two steps down the memetic supply chain of the rose quartz and serenity blue register.

[13/02/2018 01:49 GMT +08]

Here, I am reminded of the communal delousing that Xin initiated the night before a few were due to return to Singapore and while a few of us were documenting the exhibition. Ideas, lice... Hell hath no furry like a wildfire doused, these flickering embers of a muttering retreat.

In viscous time, you grow accustomed to each others’ ways of being, maybe even rely on someone else for clarity or levity. In the thick of things, ambling is not impossible - it just takes double the effort. You are embroiled. In what, however, is not so clear. But it sure is sticky.

Kenneth

there is no joe888 or youtiao666 in the embers of a dying rose. no points to be scored, no games to be won, only magical thoughts you can slip under your paws. there is no fade into the bg or wallflower selfies (t)rolling up in the throes of “partition, please”, no marketing of second-guesses, no unpacking of serfdoms, only hawking secondhand anxieties two steps down the memetic supply chain of the rose quartz and serenity blue register.

[13/02/2018 01:49 GMT +08]

Here, I am reminded of the communal delousing that Xin initiated the night before a few were due to return to Singapore and while a few of us were documenting the exhibition. Ideas, lice... Hell hath no furry like a wildfire doused, these flickering embers of a muttering retreat.

In viscous time, you grow accustomed to each others’ ways of being, maybe even rely on someone else for clarity or levity. In the thick of things, ambling is not impossible - it just takes double the effort. You are embroiled. In what, however, is not so clear. But it sure is sticky.

Kenneth

Lingering Lines (in Varying Degrees of Tension): Tracing Waste Circuits in Yogyakarta

A landfill imaginary: heaps upon heaps of desiderata emptied onto a milky chaos: a surround smell. The stink miasma wafts under torrents of rain and heat. The nose is not a device to switch off, neither is it an organ that closes nor retracts, it has no defense mechanism. Your feet sinks into a slurry of miscellany, it becomes an imperceptible fragment with the other scraps of plastic straws, plastic bags, leftover vegetables, chunks of rubber, a styrofoam cup, a bottle cap, packaging of a laundry detergent, a head of a toothbrush, hundred particles of soil, or dirt, clumped between hairs, the plant entangles its roots. The landfill is a frontier, a flat earth without frame, horizonless.

A Provisional List of Actors in the Waste Circuits of Yogyakarta

- TPST Piyungan administrative office

- Waste workers in TPST Piyungan

- Managers or middlemen in TPST Piyungan

- Caretakers

- ‘Weeds’

- Insects: flies, dragonflies, beetles, ants

- ‘Pests’

- Toxins and leachate

- Villagers around TPST Piyungan (who may or may not work in the landfill)

- Cattle

- Recycling companies

- Gases: methane, carbon dioxide, oxygen and other simple hydrocarbons

- Bacteria and viruses

- Tourists; the tourism industry

- Ministry of Public Works, government of the Special Region of Yogyakarta

- Consumers

- Tropical weather

- Etcetera

The word ‘waste’ comes from vastus, with the same Latin root as the word ‘vast’ and its vacant neighbours, vanus, vaccus and the verb vasto, ‘to make empty or vacant, to leave unattended or uninhabited, to desert’. Early usage of the word ‘waste’ suggests a dual connotation of immensity and emptiness: unpopulated country, the enormous, desolate regions of desert or wilderness. Since waste is imbued with the terminal conditions of valuelessness, finitude and dissolution, the landfill is seen as a crypt where the final fate of things rest, a space outside of the temporal punctuations of human-time and teleology. Thus, the landfill feels unthinkable, not because it is insensible but rather, over-sensible, saturating our response-ability with its intense, reticulating sensorium that exceeds human proportion. But to read the landfill as a void, chaos, total disorganisation, is to deny any response. The reading of the landfill-as-chaos is ironically reductive, a lip service to complexity.

On soft/WALL/studs’ research period in Yogyakarta with Cemeti, various constellations of the group visited TPST Piyungan (Tempat Pembuangan Sampah Terpadu, or integrated waste treatment plant) to study the region’s waste cultures, communities and infrastructure. Less than a timeless landscape, TPST Piyungan was bustling with activity. Clusters of waste workers, a sickle in their hand, gleaned the banks of the landfill for aluminium tins, glass bottles and plastics of all variety. Makeshift huts of canvas, umbrellas and spare wood served as sorting stations. Herds of goats and cows devotionally grazed the surface of the landfill, with plants flourished along its streams, salvaging the leftovers of nutrient modernity.

At the risk of romanticising the landfill as an agricultural idyll, these workers work in potentially toxic conditions under an informal wage labour system. At least half of the waste workers of the estimated 450 total are also domestic migrants, coming from towns outside of Yogyakarta, such as Monosari. They are tolerated by the landfill’s administration, rather than governed or provided for. For many, the work is an opportunity that spreads by word-of-mouth within social networks of friends and family. It was mentioned that despite state investments into medical waste disposal technologies in hospitals, some medical waste end up at TPST Piyungan due to infrastructural gaps. One waste worker we met works into the night with a headlamp. Even though the landfill is officially designated as a controlled landfill to maximise space and reduce environmental degradation, an administrator we interviewed jokingly remarked that he wasn’t certain if the landfill practiced open dumping now.

A Story of Landfill Gases, Rain and Bacteria

In the early morning of 21st February 2005, villagers living near the massive Leuwigajah dumpsite in Bandung, Indonesia awoke to the sound of three muffled blasts. In an avalanche of melting plastic, fire and refuse, 143 people and 71 houses were buried under trash heap that extended 1000 metres and rose up to 9 metres. The residents were mostly waste workers who picked daily at the dumpsite. The avalanche has been caused by an unexpected collaboration of aerobic bacteria, gas buildup within the waste mass and heavy rainfall. National Garbage Care Day held on 21st February was initiated in remembrance of this incident.

A Story of Villagers around TPST Piyungan

A stream of garbage trucks adds 500 tonnes of waste into TPST Piyungan daily. In 2015, villagers around the landfill barricaded its entrance for a few days, seeking higher compensation from the state. The act of protest caused an administrative shift of landfill from the municipal authority to the regional government. The administration not only manages technical issues within the landfill, but more so recently, they mediate social conflicts. On the car ride to the landfill, we saw a banner that wrote: “Bantul: where dreams come to die.”

At Pasar Ngasem, garbage collectors sorted assiduously on top of a truck, compressing unruly clumps of stuff into a packed heap. Pak pointed out a collector’s motorcycle installed with baskets and frames, which were filled with potentially valuable items, such as spare parts, recyclables and other paraphernalia, from the waste they filter through. Not everything in the bin goes to rest at the landfill. Some end up at Pasar Senthir, a secondhand market that sells an array of tchotchkes, wholes and their parts, priced on a whim and lowered on your bargaining tactics. No item is too broken or dirty to be loved here. Others end up at ‘waste banks’, municipal recycling stations where residents could deposit their recyclables for some money. Even at TPST Piyungan, plastics of every assortment are sold to recycling companies to make other plastic bags or asphalt for road works. But where exactly are these recycling companies, the waste worker we interviewed did not know.

Like the dumps, waste banks and secondhand markets scattered across the city, Piyungan is one node of filtration that allows waste to saunter in and out of the circuit of overlapping value regimes. Asking the same question (“where does this go afterwards?”) to garbage collectors, caretakers and sanitation workers encountered during my trip, I received staccato strokes of waste-lines that formed an ersatz map of the city’s refuse underbelly.

“I leave the trash bags on the front yard every morning, where they are cleared every Friday. And afterwards—“ To begin to think through waste is to take narrative risks, to take imaginative leaps beyond the capitalist plot of manufacture-use-disposal, and to sense them as things that shimmer across regimes of value, desire and utility. To render a moving thing: where does it go, where does it go. It is an ethics of sensing that thaws the imaginary of a frozen landfill, thinking in entangled lines, storylines, that tendril and spread, tighten and slacken with one another. Could we begin to diagram waste circuits as a bundle of lines, rather than a network of terminal points with assumed connections. Pulling at one thread reveals the knots and loops of many others. Rather than a black hole of modernity that the lifeline of all things lead to, take the landfill as a single line among other lines in media res, middling around. And let its perfume linger awhile.

Marcus